Mass confusion greets Officers Williams and Sawyer as they stare through their tinted squad car window, but maybe that’s to be expected on this unusually humid South Florida morning. “Don’t look at me,” laughs Williams, “you’re the new guy.

A potential disturbance between wealthy, stay-at-home moms and their nannies is exactly what you should be investigating.” Sawyer attempts a joke, “I think they may be au pairs, not nannies.” Williams laughs then gently gives an order, “you pronounced ‘awe-pear’ with an accent. All the better reason for you to investigate.”

Officer Sawyer accepts defeat and exits the patrol car, walking cautiously toward the Frond’s Bay Municipal Playground. The unfolding scene seems ludicrous. The kindergarten-age children, of which there are many, cram together on the benches of several picnic tables. Wielding sticks in both hands, they poke at Lego blocks, balls of paper, and each other.

Adults speak and shout in accented words bearing dialects from numerous states and countries which echo off the Japanese Fern Trees that border the park, creating Babel-like hysteria that conflicts with the Eden-like bubble of Frond’s Bay. The adults chastise the children, stating “stop that” and “sin tirar” in varying degrees of forceful tones. The sticks turn into projectiles and fly from one table to another.

After side-shuffling through the staggered fence entrance, one of these projectiles hits Officer Sawyer’s shoulder and lands perpendicularly on his shoe.

“A chopstick?” exclaims Officer Sawyer aloud through chuckles of confused laughter.

“Oh my god!” exclaims a mother running his way in an accent more native to Long Island than any part of Florida, “I’m so sorry, officer, I can’t believe my little brat did that.”

“My name’s Austin, and it’s okay.” He pauses to pick up the projectile before holding and turning it with his fingers. The sparkle from the woman’s jewelry catches him off-guard. He shakes his head and blinks before asking, “are all those kids using chopsticks?”

“You have no idea,” she replies, sensing disapproval and feeling compelled to over-explain. “The school changed its admission requirements. It used to be stacking blocks and cutting a few shapes with scissors, but now the kids have to pass a chopsticks test.”

“A what test?”

“The school says it’s based on research with Chinese children.” She pauses to speak in a voice intended to mock the school administration.

“Using chopsticks triggers higher level thinking skills at an earlier age and provides our students the aptitude necessary to successfully navigate not only the challenging curriculum here, but also at the many highly competitive colleges and universities they will attend, ensuring they are global citizens prepared to face America’s 21 st century challenges.” She returns to her own voice to add, “I swear the guy wants us to sing ‘God Bless America’ when he finishes talking.”

“But,” interjects Austin before pointing his one chopstick at the children, “these kids look four or five.”

“Mine just turned five,” declares the woman before placing her hands upon her hips and declaring in Long Island splendor, “how is he supposed to learn to use chopsticks? He’s barely coordinated enough to pick his nose.”

“What school is doing this?”

“Frond’s Academy,” states the woman in a tone that implies Austin should have known because there really isn’t any other school in this area of South Florida unless you drive your kid over the intercoastal bridge to the public school, and no one around here does that.

Austin pauses to fully absorb the scene. By now, women scramble to confiscate Legos while others offer both threats and potential rewards to settle the children down. These are desperate times, thinks Austin, as a parent follows, “stop that or there’s no Xbox when we get home” with, “we can stop at Sun-Daes, and you can get an extra scoop – even Oreo’s mixed in” to get her child under control.

“My wife has an early childhood degree,” says Austin, attempting to help. “What I remember from listening to her recite the various theories and stuff, you’re doing this all wrong. There are way too many kids trying to learn at once.”

“Can your wife use chopsticks?”

“Yes,” Austin adds, “her mom’s actually from Hong Kong,” then wonders why he said that.

“She is,” states the woman while staring past Austin’s bright blue eyes to the great idea she sees materializing in the Japanese Fern Trees behind him. She speaks as one divinely inspired: “Is she available?” Her eyes lock onto Austin’s as she completes her brilliant plan, “you know, for tutoring.”

“Tutoring in chopsticks?”

“Exactly. I’m sure your wife’s native abilities will be much better than our Hispanic au pairs.” She feels compelled to whisper the rest to Austin. “Mine’s from Cuba. I don’t think she’s ever eaten Chinese food.”

The woman texts Austin her number before he returns to the squad car. The few, still defiant children have been corralled around the swings. With the exception of one child who insists on standing on the swing, Austin assumes everything will be alright. “Chopsticks may be beyond that kid’s abilities,” laughs Austin as he relaxes into his seat.

“Did you get the situation under control?” asks Williams while they both watch the child standing on the swing gain momentum and trigger terrified looks in the adults. “I think so,” replies Austin as he wonders what to tell his wife about all this.

***

Austin’s wife, Beth, does not think picnic tables in Frond’s Bay Municipal Park is a location conducive to learning. She suggested much smaller groups at an indoor space, and several moms offered their homes. After negotiations tactful yet firm enough to release prisoners from terrorists, Beth created a schedule utilizing two different houses without bruising anyone’s ego.

Now, Beth sits with one of the children who’s been struggling more than the others. “You can do it, Tommy,” encourages Beth, “just watch me and do what I do.” She slowly grasps the chopsticks and picks up an object while softly singing “the chopstick song,” as she likes to call it: this is how we chop with sticks, chop with sticks, chop with sticks; this is how we chop with sticks, to pick up the gummy bears.

“My Tommy, I swear to god,” comments his mother.

“He just needs more time,” offers another mom. Her daughter, Maya, picks up and consumes gummy bears with robotic efficiency, making her mom feel proud but a little awkward, too. “And, you know, girls are quicker learners than boys at this sort of thing.”

“No, he’s hopeless just like his father, who asks for a fork at Chiu Fan Gardens; it’s so embarrassing.”

“Look,” the other mom points toward Tommy while grasping his mother’s wrist with her other hand. “I think he’s got one.”

The room goes silent. Even Beth stops singing and holds her breath, worried an exhale will ruin the moment. A yellow gummy bear wiggles between the chopsticks as Tommy struggles with the exact amount of pressure needed to keep the gummy bear still. The chopsticks and gummy bear hover above the table, an inch high at most. Adult eyes bulge and cease blinking as Tommy lifts the gummy bear several inches higher. For a long, long second, he appears frozen in panic.

His motionless body extenuates the twitching of the chopsticks, making the gummy bear’s belly jiggle.

“You got this, Tommy,” whispers Beth.

With a resolve not seen among most five-year-old boys, Tommy nods and exhales. The gummy bear stabilizes before elevating further above the off-white table, creating a shadow from the overhead, track lighting. He smiles at Beth, eyes wide and desperate for approval.

“You’re almost there, Tommy,” whispers Beth, terrified that, like several times already, he will send the gummy bear flying across the room before it reaches his mouth. “Now, place it in your mouth. Then, you get to eat it.”

Tommy smiles and nods. Opening his mouth wide, he guides the gummy bear in between his lips before placing so much of the chopsticks into his mouth that everyone fears he may choke. He doesn’t, sliding them out of his mouth while triumphantly swallowing the gummy bear whole.

“That was amazing,” exclaims Tommy’s mother, cheeks flushed and hands trembling. “He can get into Frond’s Academy now.”

“It’s a good feeling,” adds the other mother, “isn’t it?”

“Better than sex,” she states bluntly, “I’m giving her at least an extra hundred bucks for this.”

***

Beth and Austin’s two-bedroom condo looks nothing like the home she returns from. Not only is it on the less-desirable side of the intercoastal bride; their tiny, dated unit also reflects the madness of new parents trying to balance their pre-child lives with their post-baby realities. A second-hand elliptical, adjacent to the sliding glass door that leads to a small patio, is covered with onesies and blankets, rendering it completely unusable.

Next to the elliptical, a mechanized baby-rocker blocks the path to the patio, where several plants die the slow death of neglect. The weathered furniture accumulates dirt, dust, and leaves from the trees in the courtyard.

“Shh,” mouths Austin while placing his index finger over his lips. “Sorry,” mouths Beth in response, quietly closing the door behind her.

Beth steps softly toward Austin, extending her arms to take their sleeping child. With a skilled mother’s grace, Beth lowers the infant into the mechanized rocker. She turns the knob to “low” to add some background noise and hopefully prevent their child from prematurely ending her nap.

“How was tutoring?” asks Austin quietly.

“I don’t want to see another gummy bear for at least a month,” she whispers, “and I could use a drink.”

Austin chuckles while lifting himself from their oversized chair and following Beth into the kitchen. She has a full glass in hand before he gets there.

“You want a glass?” She asks as a wad of bills fall from her open hand onto their kitchen table.

“Holy crap! You should be drinking champagne.”

“This is the good pinot, so it’s ok.” Beth laughs as she swirls the wine around the rim of the glass before taking a sip and continuing, “but, I don’t know, Austin.”

“What do you mean?”

“The moms want me to keep tutoring their kids, not just until the admissions test but after – through the summer. I thought this would be a one-time deal, two-times at most.”

“Isn’t that great news?”

“What about Josephine? You were off today, so we didn’t need a babysitter. We’ll have to find one next time, and the time after that, and after that, it just feels rushed.”

“It won’t be too hard, right? Mrs. Jenkins has been offering to help since she found out you were pregnant.” Austin pauses to read Beth’s reaction. “We won’t find a better person.”

“She would be great,” replies Beth before sipping again and placing the wine glass next to the money. “And I was planning to go back to work. That’s not what’s bothering me.”

“Then,” asks Austin quietly, “what is it?”

“I could make as much tutoring these kids as I’d make as a social worker, maybe even a little more.”

“Yeah,” sighs Austin before continuing, “it’d be terrible to make more money, especially in cash.”

“That’s not it, Austin,” His sarcastic tone elicits a cold stare from Beth. “That’s not it at all.”

“I’m sorry,” says Austin apologetically, “what’s bothering you about this?”

“Josephine is never going to Frond’s Academy. The pre-school costs twenty-seven thousand dollars a year, and that doesn’t cover the extended-day coverage, uniforms, or supplies.”

“You researched the costs?”

“I got stuck in bridge traffic and checked out the school’s website.” She takes another sip. “I’m not sure how comfortable I am helping kids get into a school that Josephine will never attend, especially when we decide to have baby number two.” She smiles at the thought.

“I never thought about that.” Austin smiles, too.

“I hadn’t, either, until driving home.”

“I guess I figured our kids would attend public school.” Austin gestures with his open palms and attempts a smile. “We survived and turned out okay, didn’t we?”

Beth hears Austin but looks past him, out the kitchen toward the baby clothing covered elliptical. Silence ensues until the gentle whir of the mechanized baby rocker reverberates gently off the walls. They bought it used, so the motor strains and increases in volume the longer it runs. Beth moves her gaze to the stack of cash on the table, trying to compute how many of next month’s bills she just paid and if maybe there’s enough for a decent dinner somewhere and a babysitter.

Looking toward Austin, she senses a crisis coming as navigating motherhood, employment, and her child’s future never seemed so complicated. “Would you quit your job for something like this?”

About the Writer: Originally from Fairfield, Connecticut, Michael Mulvey is a happily married father of four living in Jacksonville, Florida. His publications include: “Replacement Theory,” winter 2023 issue of TheBeZine; “Safeharbour No More,” December 2023 edition of Portrait of New England; “Town Centers aren’t Shopping Malls,” Dumbo Press in March of 2024; “Our New Religion,” New English Review in November of 2024; and “Safety,” New English Review in February of 2024.

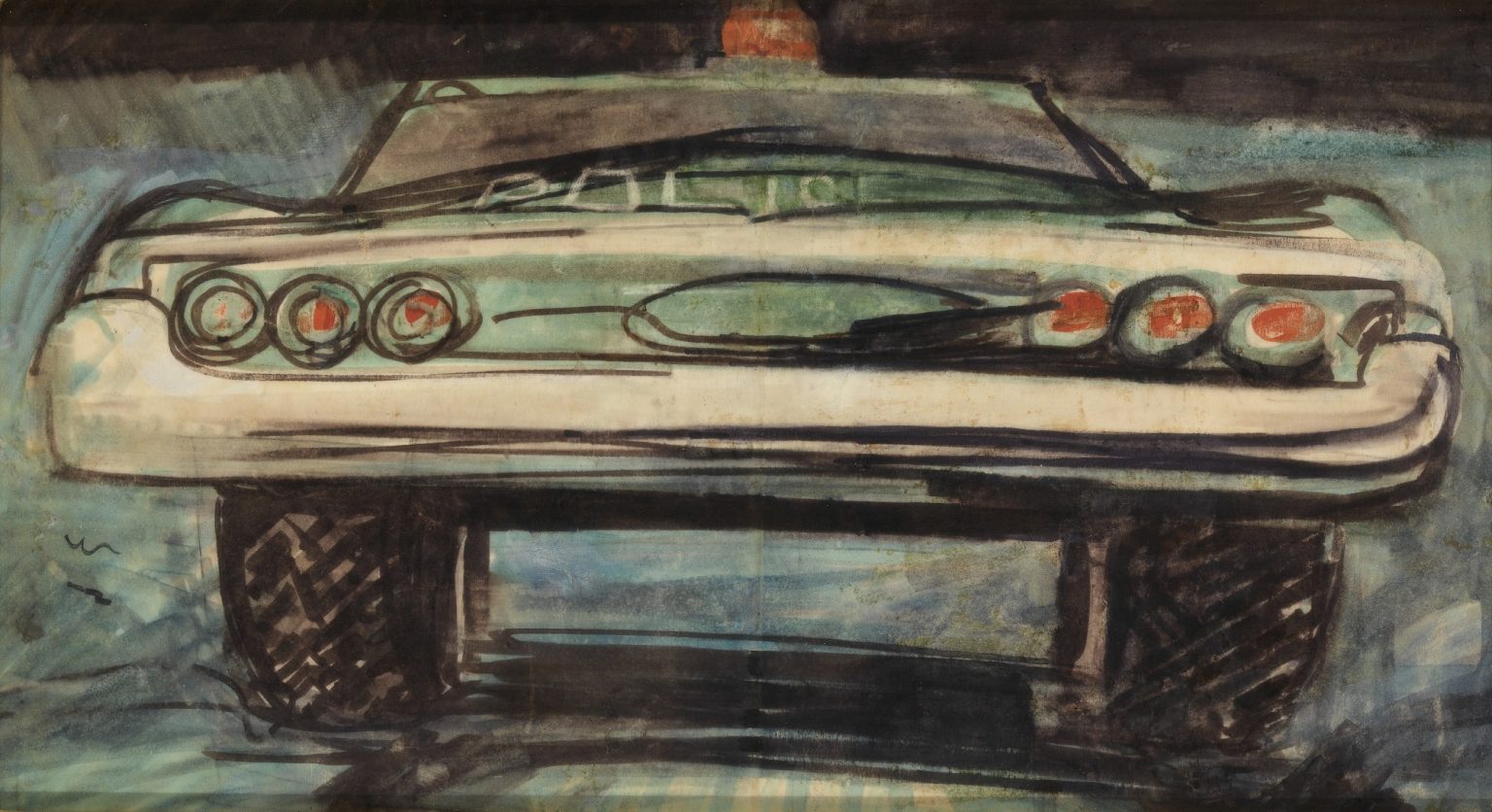

AI art produced by Krin Van Tatenhove